Fact Sheet · The Situation of human rights in Iran

Fact Sheet · The Situation of human rights in Iran

Download a PDF version of the fact sheet here.

VIOLENT REPRESSION OF PEACEFUL PROTESTS

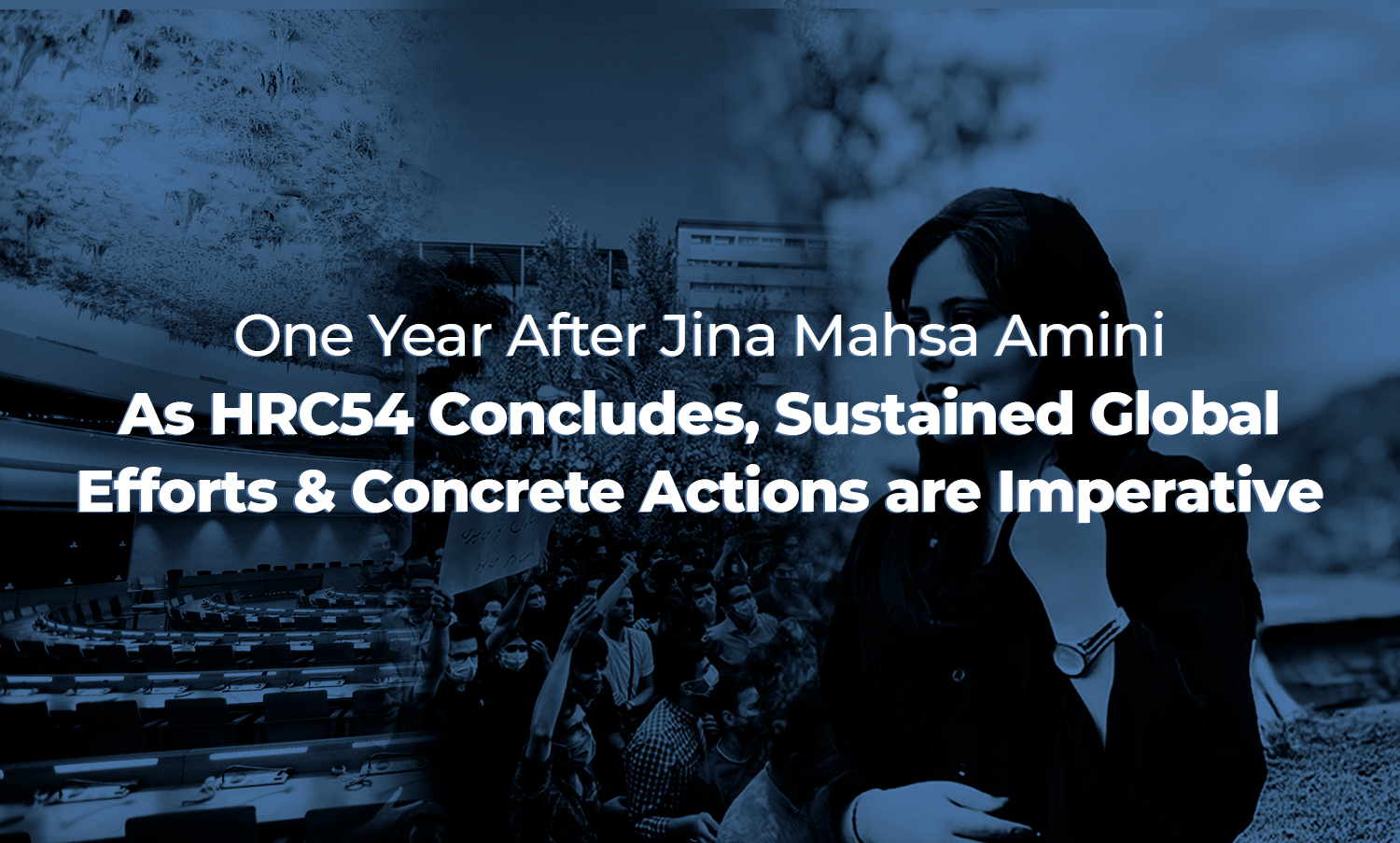

Over the last six months, scores of Iranians have taken to the streets as part of an unprecedented wave of nationwide protests triggered by the custodial death of Jina Mahsa Amini. Protests rapidly spread to all of Iran’s 31 provinces.[1] Slogans have been calling for justice, sweeping political change, and respect for human rights, echoing prior demonstrations spanning a decade.

As the events unfolded, Iran’s authorities and security forces systematically resorted to the widespread use of lethal force and live ammunition against unarmed, peaceful protesters, including at close range.[2] As of February 2023, human rights groups reported:

| Over 480 individuals were killed during the protests, including at least 64 children.[3] More than half of the total number of persons killed are from Baluchi and Kurdish-populated provinces (at least 130 Baluchis and 125 Kurds have been killed as of December 31, 2022, including 13 children).[4] |

| More than 19,000 civilians have been arrested and detained since September 2022, according to HRANA[5], subjected to torture and other ill-treatment.[6] |

| On March 13, 2022, the head of the judiciary announced that at least 22,000 protesters were subject to amnesty.[7] The list of those subject to amnesty and release dates is not publicly available, although authorities have reportedly affirmed to the media that the pardon would exclude dual citizens, individuals facing the death penalty, “unrepentant” prisoners, alleged foreign collaborators, and individuals allegedly linked to so-called “hostile” groups. |

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT AND THE RIGHT TO LIFE

General statistics

According to ECPM, the Islamic Republic is the state with the highest execution rate relative to its population.[8] In 2022 over 500 executions were reported.[9] Members of minorities are disproportionately represented in execution statistics. The Baluch people, who constitute 2-6% of Iran’s total population, represented at least 18% out of all those executed in the country, often for drug-related offenses and moharebeh.[10] According to IHRNGO, between 2010 and 2021, more than half of those executed for affiliation to banned political and militant groups were Kurds.[11] Most recently, Mohayyedin Ebrahimi was executed on March 17th, 2023 for his alleged links with a Kurdish opposition political party.[12]

| At least three executions of alleged child offenders were documented in 2022. At least 70 individuals have been executed since 2010 based on charges for offenses allegedly committed when they were children.[13] |

| On 14 January 2023, Alireza Akbari, a British-Iranian national, was executed following a conviction for spying and other national security charges based on forced confessions extracted through torture.[14] On 21 February 2023, Jamshid Sharmahd, an Iranian-German dual national, was sentenced to death by a Tehran Revolutionary Court on the charge of “corruption on earth” after being reportedly forcibly disappeared and taken to Iran in August 2020.[15] |

Protest-related statistics

| As of February 2023, at least four individuals were executed based on charges relating to the protests since 16th September 2022: Majid Reza Rahnavard, 23 years old; Mohammad Mehdi Karami, 22; Mohsen Shekary, 23, and Seyed Mohammad Hosseini, 39. Iranian authorities left Majid Reza Rahnavard’s bound body on public display in Mashad, hanging by his neck on a construction crane. High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk denounced the Government’s “weaponization of criminal procedures to punish people for exercising their basic rights.”[16] |

| Human Rights groups identified more than 100 individuals facing charges for their participation in the protests and that carry the death penalty as of February 2023.[17] Among them, 19 alleged protesters have already been dealt death sentences. |

WOMEN’S AND GIRL’S RIGHTS

According to the Global Gender Gap Index, The Islamic Republic of Iran ranks 143 in gender equality out of 146 countries surveyed.[18] As asserted by ten UN experts in October 2022, the “continuum of long-standing, pervasive, gender-based discrimination [is] embedded in legislation, policies, and societal structures. All of which have been devastating for women and girls in the country for the past four decades.”[19]

Despite the international community’s calls, the Iranian Government has persistently delayed the adoption of legislation that sought to protect women’s and girls’ rights while fast-tracking those that actively undermine their human rights.

| A bill aimed at tackling violence against women has remained in legislative limbo since 2012. The Iranian Parliament, Judiciary, and President’s Office have been caught in an unyielding cycle of removing essential provisions from the draft. |

| In November 2021, the Guardian Council ratified the ‘Youthful Population and Protection of the Family law,’[20] which aims to boost the country’s fertility rate in Iran. The law has been denounced by UN experts as being clearly in “contravention of international law,” violating “the rights to life and health, the right to non-discrimination and equality, and the right to freedom of expression.” [21] |

| A draft Bill on discretionary Punishments is currently under legislative review since December 2022. [22] According to the available draft, the bill not only continues to impose compulsory veiling on women and girls but also seeks to expand the scope of the “offenses” and strengthen sanctions for failure to abide by the criminal requirement. Additionally, the draft bill effectively seeks to transform non-state actors, including managers and business owners, into agents of enforcing compulsory veiling. On January 10, 2023, the Prosecutor General’s Office issued a decree to the country’s police forces ordering them to “firmly confront” women and girls not wearing the veil. |

Despite the international community’s calls, the Iranian Government has persistently delayed the adoption of legislation that sought to protect women’s and girls’ rights while fast-tracking those that actively undermine their human rights.

DUE PROCESS AND FAIR TRIAL STANDARDS

The Islamic Republic “weaponizes” its legal and judicial systems in the courts to punish those who express dissent against the State in whatever shape or form.

According to High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk, executions of protesters were carried out following “expedited trials that did not meet the minimum guarantees of fair trial and due process required by international human rights law binding on Iran, making their executions tantamount to arbitrary deprivation of life.” A Revolutionary court sentenced Mohammad Mehdi Karami to death in just one week. He was executed on January 7, 2023, only two months after his arrest.

According to ABC, since September 2022, authorities arrested at least 48 lawyers and sentenced at least 10 for seeking to represent detained protesters or to raise awareness of detainees’ rights.[23]

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND THE PRESS

According to Freedom House’s “Freedom on the Net 2022” index, Iran’s online space is “Not free.”[24] The Parliament is currently reviewing the User Protection Bill, which would further restrict freedom of expression online and tighten regulations on foreign and domestic online platforms, effectively “isolat[ing] the country from the global internet,” according to UN experts.[25] Even though the Bill is still under review, the Supreme Council of Cyberspace has already issued directives that, in effect, implement some provisions of the Bill.[26]

Authorities target journalists and media practitioners with intimidation, harassment, arbitrary arrests, detentions, and imprisonments solely for performing their work. According to HRANA, at least 79 journalists and media practitioners have been arrested since the beginning of nationwide protests.[27] In 2022, Reporters without Borders ranked Iran 178 out of 180 countries in its World Press Freedom Index.[28]

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RIGHTS

Many provinces in Iran where ethnic and religious minorities are concentrated, such as Khuzestan, Kurdistan, and Sistan-Baluchestan, are impoverished and underdeveloped, with higher poverty rates and poorer health conditions overall. According to Minority Rights Group, Sistan-Baluchestan, where the Baluchi ethnic group forms the majority of the population, is one of Iran’s poorest provinces, with some of the highest illiteracy and infant mortality rates in the country, while an estimated two-thirds of the province lack access to clean water.[29] Similarly, Khuzestan, comprising mainly Arab Iranians, has some of the lowest socio-economic indicators in Iran and is believed to have one of the highest rates of suicides due to poor social and economic conditions affecting the local population.[30]

In law and practice, members of ethnic and religious minorities are excluded from high-level positions in the government, judiciary, and military. They are likewise underrepresented in senior and mid-level posts in many fields of employment. Those seeking employment in the public sector must meet the requirements of a mandatory screening process which assesses one’s “allegiance” to Islam and the Islamic Republic of Iran, known as gozinesh. Members of ethnic and religious minorities are regularly denied employment based on the gozinesh process.

Corruption: Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index ranks Iran 147 out of 180 countries.[31] Some of the slogans in popular protests throughout the year denounced pervasive corruption. The absence of financial transparency within a country directly maps to an increase in both economic and political petty corruption and grand-scale corruption on a national and international scale.[32] Iran does not possess a comprehensive code addressing financial transparency and anti-corruption.

[1] https://www.en-hrana.org/a-comprehensive-report-of-the-first-82-days-of-nationwide-protests-in-iran/

[2] https://www.iranrights.org/memorial/story/-8587/minu-majidi

[3] https://twitter.com/HRANA_English/status/1627447179907420161 ; https://iranhr.net/en/articles/5687/

[4] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/5687/

[5] https://twitter.com/HRANA_English/status/1627447179907420161

[6] https://www.en-hrana.org/a-comprehensive-report-of-the-first-82-days-of-nationwide-protests-in-iran/

[8] https://www.ecpm.org/en/barometer/

[9] HRAI has documented 565 executions in 2022 (299 executions documented in 2021); ABC has documented 576 executions in 2022 (317 executions documented in 2021).

[10] https://www.hra-news.org/periodical/a-131/#A08 ; https://www.iranrights.org/library/document/4000

[11] https://www.ecpm.org/app/uploads/2022/08/Rapport-iran-2022-gb-260422-MD3.pdf

[12] https://kurdpa.net/en/news/2023/03/17

[13] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/4727/) and https://iranhr.net/en/articles/4727/)

[14] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-64273520

[15] https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde13/5909/2022/en/

[16] https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/01/respect-lives-voices-iranians-and-listen-grievances-pleads-un-human-rights

[17] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/5687/

[18] The Index framework surveys 1) Economic Participation and Opportunity, 2) Educational Attainment, 3) Health and Survival, 4) Political Empowerement. https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2022/in-full

[19] https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/10/iran-crackdown-peaceful-protests-death-jina-mahsa-amini-needs-independent

[20] http://nazarat.shora-rc.ir/Forms/frmShenasname.aspx?id=Bffc3DPSti0=&TN=l7tLyhyOobj0SooAFUE3m68PnpG7MruN

[21] https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/01/iran-repeal-crippling-new-anti-abortion-law-un-experts?LangID=E&NewsID=27817

[22] For the text of the draft bill, please see: https://bit.ly/40hCCjZ

[23] https://www.iranrights.org/newsletter/issue/130

[24] https://freedomhouse.org/country/iran/freedom-net/2022

[25] https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/03/un-human-rights-experts-urge-iran-abandon-restrictive-internet-bill

[26] https://www.article19.org/resources/iran-draconian-internet-bill/

[27] https://www.en-hrana.org/journalist-saeedeh-shafiee-arrested/

[28] https://rsf.org/en/ranking. This score is calculated on the basis of two components: 1) a quantitative tally of abuses against journalists in connection with their work, and against media outlets; 2) a qualitative analysis of the situation in each country or territory based on the responses of press freedom specialists (including journalists, researchers, academics and human rights defenders) to an RSF questionnaire available in 23 languages.”

[29] https://minorityrights.org/wp-content/uploads/old-site-downloads/download-1087-Seeking-justice-and-an-end-to-neglect-Irans-minorities-today-English-version.pdf

[30] https://minorityrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/MRG_Brief_Baloch_ENG_Nov22_CORRECT.pdf

[31] “The index ranks 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public-sector corruption according to experts and businesspeople. It relies on 13 independent data sources and uses a scale of zero to 100, where zero is highly corrupt and 100 is very clean.” Iran’s score is 25/100. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022/index/irn