For more on the Universal Periodic Review of freedom of expression, read Impact Iran’s joint submission with ARTICLE 19, PEN America, and All Human Rights for All in Iran here.

| Universal Periodic Review of Iran 48th Session · January 2025 |

Alignment of Domestic Legal Framework with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

The Iranian Constitution does not protect the rights to freedom of opinion, expression and peaceful assembly in line with international law. It fails to protect these rights when they are deemed “harmful to the principles of Islam or the rights of the public” (Art. 24), “injurious to others” or “detrimental to public interests” (Art.40). These vague and overbroad conditions stand in clear contradiction to Article 19 ICCPR. In 2023, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention observed “that vague and overly broad laws are consistently used in the Islamic Republic of Iran to criminalize the exercise of the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly” a situation it had already denounced in 2021 and 2018.

Instead of taking steps to bring laws in conformity with their international obligations, authorities have introduced new legislation further violating them. For example, in January 2021, the Parliament added two supplementary provisions to the Islamic Penal Code criminalizing “insulting legally-recognized religions, Islamic branches, and Iranian ethnicities” and, inter alia, “deviant educational or proselytizing activity that contradicts or interferes with the sacred religion of Islam.” Concretely, these amendments provide new tools for authorities to target dissidents and the already persecuted minority communities under the pretext of preserving national harmony.

Freedom of Expression Online

The FFMI concluded that the “gradual closing of the digital space over the last two decades, has increasingly become part of the Government’s armoury of tools and tactics for silencing and punishing those protesting or acting in solidarity as well as shielding themselves from accountability.”

Iran’s domestic legal framework allows a wide range of Government security institutions unchecked control over access of people in Iran to cyberspace as well as regulating content. The Computer Crimes Law restricts and criminalizes content on grounds of “chastity” and “public morality”, “propaganda against the system” or content against officials and governmental and public institutions, in violation of Article 19(3) ICCPR.

The Parliament is currently reviewing the “Protecting Internet Users’ Privacy Bill,” which would further restrict freedom of expression online and tighten regulations on foreign and domestic online platforms, effectively “isolat[ing] the country from the global internet,” according to UN experts. In January 2023, the Government reported that the “Regulatory System for Cyberspace Services Bill” was “sent in the form of a draft to research centers for further examinations.” If enacted, the Bill risks leading to increased or even complete communication blackouts in Iran, and increased bandwidth limits, and further control over access to online information as well as to digital technologies and online platforms.

Iran’s National Information Network (NIN), a project which seeks notably to force websites and online services, including social media and messaging platforms, to locate their servers inside Iran -thus limiting access to global internet traffic- for greater government control and surveillance online, has had a major role in facilitating Internet shutdowns in Iran, including during critical moments like protests.

This period has seen intensified restrictions on internet access, including targeted shutdowns, bandwidth throttling, mobile curfews, and censorship of secure communication platforms, alongside the criminalization of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs). Surveillance and online harassment, facilitated by tools like the SIAM system, facial recognition, and peer-reporting apps such as Nazer, have been used to suppress protests and further oppress women’s rights.

| Recommendation |

| “Revise and amend legislation unduly restricting freedom of expression to ensure that criminal laws are not used to silence dissenting voices – including through the blocking of websites and online resources and through Internet shutdowns – and ensure that any restriction on the exercise of freedom of expression complies with the requirements of the Covenant.” (Human Rights Committee, Concluding Observations, October 2023, para 50 (d)) |

Protests & State Response

Since Iran’s last UPR in November 2019, Iran’s authorities repeatedly and violently suppressed protesters who took to the streets against political repression, corruption, high inflation, and worsening environmental situation and demanded structural change, freedom, justice, accountability and equality. Protests were met with patterns of unlawful force, including lethal force, by state authorities who used live ammunition, metal pellets, and military-grade weapons, leading to unlawful killings of women, men and children and severe and irreversible injuries including blinding.

Authorities conducted mass arrests and subjected many detainees to trials that bore no resemblance to meaningful judicial processes resulting in harsh sentences and executions. Authorities have taken concerted and deliberate action to conceal human rights violations and crimes under international law, including through widespread internet shutdowns, while silencing those seeking justice. Minorities such as the Ahwazi Arabs, Kurds, and Baluchis were disproportionately affected by violent protest crackdowns.

| Recommendations |

| “Ensure that individuals who exercise their right of peaceful assembly are not prosecuted and punished on the basis of arbitrary charges for exercising their rights, and that those detained on such charges are immediately released and provided with adequate compensation” (Human Rights Committee, Concluding Observations, October 2023, para 52 (b)) |

| Immediately cease all use of unlawful force, including lethal force and firearms against, and enforced disappearances, torture and other forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, including sexual and gender-based violence against and arbitrary detention of those exercising their rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association. |

Human Rights Defenders, Journalists, and Lawyers

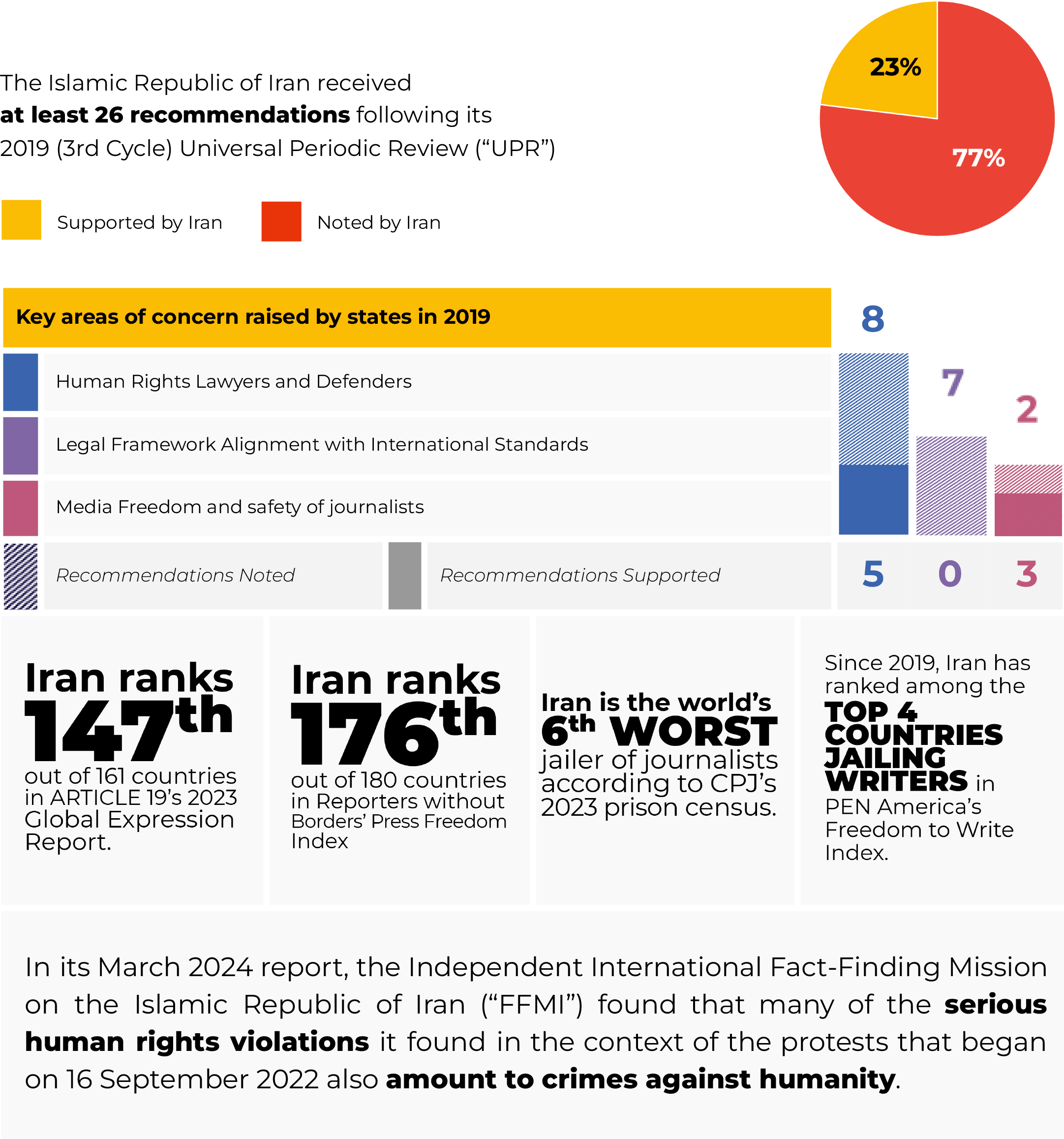

Since Iran’s 2019 UPR, authorities have systematically subjected human rights defenders, writers, lawyers, and journalists to threats, attacks, intimidation and harassment, arbitrary arrests and detention, torture and

other ill-treatment, including sexual and gender-based violence, and grossly unfair trials on national security or public order charges solely for speaking out or conducting their peaceful work. Even when released after serving long prison sentences, human rights defenders, writers, journalists and lawyers have faced bans for traveling outside the country, participating in gatherings, engaging in online communications, and exercising their profession.

| In December 2023, Iran Human Rights NGO reported on 150 cases of human rights defenders, lawyers, and journalists who had been “collectively sentenced to more than 541 years in prison and 577 lashes” solely for carrying out their work and activities since the 2022 September protests. |

| According to Reporters without Borders, there are at least 25 journalists currently in detention in Iran. PEN America records at least 49 writers currently in detention. |

The 1986 Press Law limits the publication of material deemed critical of key political figures, including the Supreme Leader and the President, thus restricting and criminalizing critical reporting. The Law lists 12 conditions under which the media may be censored, including “publishing heretical articles”, “spreading fornication and forbidden practices”, and “propagating and spreading overconsumption”.

Since Iran’s last UPR in 2019, authorities have been continuously retaliating against journalists, covering protests and police and security forces’ violence, promoting minority or oppositional viewpoints, reporting on corruption or human rights violations or criticizing the state. Violations include denial of access to legal counsel, use of torture including to extract forced confessions, lengthy detention without charge, and privacy violations.

| Recommendations |

| “Cease and prevent acts, in particular those of harassment, intimidation, and violence, against journalists, media workers, human rights defenders, and other civil society actors aimed at deterring or discouraging them from freely expressing their opinions;” (Human Rights Committee, Concluding Observations, October 2023, para 50 (a)) |